For a new three-part article series, Spencer W. Stuart further explores the stages of collecting and collections dealt with through his Lifecycles program. At the end of June, he will be delivering a one-hour virtual presentation of the series for collectors, curator/librarians, appraisal professionals, trusts & estates representatives and dealers alike. Registration is still open.

This article is part of a series:

- Part I: Lifecycles: Collecting & Collections. Part I – For the Curious

- Part II: Lifecycles: Collecting & Collections. Part II – For the Collector

- Part III: Lifecycles: Collecting & Collections. Part III – For the Collection

III. LATE STAGE COLLECTING

a. What Time Affords

Crucial to the ‘late stage’ of collecting is giving yourself adequate time to: a) consider the future of your collection (sell or donate? Keep it together or break it up?) and b) find out the cultural and commercial systems of value within which your collection exists (ultimately resulting in a strategy for deaccession).

By developing an awareness and understanding of the position one’s collection occupies, the collector can align the expectation of their collection’s future. This anticipatory procedure, informed by comprehensive cataloguing of the collection, can mitigate the potential of ‘emotional blowback’ that can result from a collector faced with not enough time to properly part from their collections. This emotional resistance can result in a collector becoming overwhelmed by their circumstances and, refuting the act of collecting, casts themselves as the ‘Obsessive/Impulsive’ Collector as outlined previously.

Just as a collector owes it to their collections to take stock and care of them through the cataloguing process, a collector does a disservice to themselves, their collection’s holdings, and those around them if they do not take the time to really consider its purpose and place within a greater context. At times, this can be difficult, however it is essential to maintaining the vital cultural work collecting provides to our communities.

b. Relatable or Eclectic?

These distinctions align with ‘Object-Elicit’ and ‘Idea Oriented’ collecting approaches. ‘Relatable’ collections consist of holdings that have precedent within a broader collecting community and thus often have markets through which comparable value can be generated and as a result have a reach that is national, if not international in terms of cultural and commercial recognition. ‘Eclectic’ collections, synonymous with ‘Idea Oriented’ collecting, by definition are incomparable. Formed on the basis of what is not represented within a culture, the individual and cumulative value of the collection’s holdings can be difficult to ascertain making them hard, if not impossible (at first), to integrate into a commercial context. That said, the impetus for the collecting of this nature, and the stories told through these collections, make them valuable to Cultural Institutions with mandates to broaden their representation of underrepresented communities or alternative forms of cultural expression.

c. Channels of Redistribution: Dealer/ Auction/ Institution/ Inheritance

With an understanding of the outside world’s awareness of your collecting interests, you can then assess the likelihood of your collection going through your desired channels of redistribution. This is the essential work of the ‘late stage’ collecting process and begins with the act of cataloguing one’s collection.

Through Dealers

The deaccessioning of one’s collection can be an emotional process and at times market dynamics that you understood as a buyer can cause confusion and frustration when you yourself are selling. With this in mind, if you decide to sell to a dealer, when they make you an offer, the amount will likely be 30-50% less than similar items recently offered on the market.

Some benefits: because most dealers specialize, their knowledge of the demand within a collecting area will result in a shorter time frame for correspondence. The objective of dealers is to cultivate long-lasting relationships with collectors and will also ensure (to some extent) that items from your collections will find a good home. That said, as most dealers want to offer exceptional material, the likelihood of them purchasing the entirety of a collection is low (in some cases selling on consignment can be arranged). Even then, your collection will not stay intact.

Use of a dealer is most appropriate for ‘Object Elicit’ collectors with little to no interest in preserving their collection as a whole.

At Auction

Also within the commercial realm of deaccessioning, auction houses are a viable option for ‘Object Elicit’ collectors who are not interested in keeping the collection together. Even more so than a dealer, auction houses are interested in pre-established collecting markets and have robust client contacts and infrastructure in place to market consigned material. In dealing with auction houses, sellers need to be aware that the infrastructure houses provide is factored into commissions that they extract from the realized price.

That said, given the environment generated by the event of the auction, on any given day your item could realize a price that exceeds the estimate. Therein lies the risk.

Not setting a reserve for items offered might result in pieces from your collection selling for less than expected. Conversely, setting a reserve too close to the low-end estimate for the item at a time where demand is low within the market can result in the lot being ‘burned’. Thus, being on record as being undesirable, the seller must wait until the lot ‘cools off’ before being reoffered.

An often-unexpected outcome to consignors is the stark reality of the auction catalogue. All of a sudden, your item is immediately extracted from your perception of it and placed temporally in relation with other items, where it might not look as great as previously thought. Stripped of its unique connection to other items in one’s collection, this can come as somewhat of a shock.

Institutions

With adequate time and a collection with a unique ‘Idea Oriented’ bent, institutions can be a viable option for the sale or donation of one’s collection.

As institutions are (by definition) made up of many actors, the development of a relationship between a collector and institution can take years. In acquiring a collection, librarians or curators evaluate collections in two ways. First, they are thinking in terms of appraisal value (i.e. market value), but also processing (i.e. staff time to catalogue). This is why it is important to be clear and direct with institutions upon initial contact about an offering.

Research which institutions have collections that relate to yours. Once established, do your homework as to what they already have, when they got it, and if they are continuing to actively acquire such material. If they seem active, identify the appropriate person within the institution to contact and have a ‘pitch’ prepared about your collection, outlining how its story might connect to other holdings they have. Within this correspondence, it will be valuable to provide the librarian or curator with as much uniformly detailed catalogue information about the collection as possible (as outlined in Part II).

Assuming a tentative agreement of interest is established during this process, it may be possible to offer items for upcoming exhibitions they might be having (as this institution will eventually serve as the collections new home). Such an offer allows librarians and curators to demonstrate your collection’s relation to the institution’s holdings for donors and administration.

As it is a process, be sure that understandings between the institution and yourself are maintained when new personnel assume positions held by people you had a pre-existing relationship with. Getting confirmations and agreements in writing can help with this step.

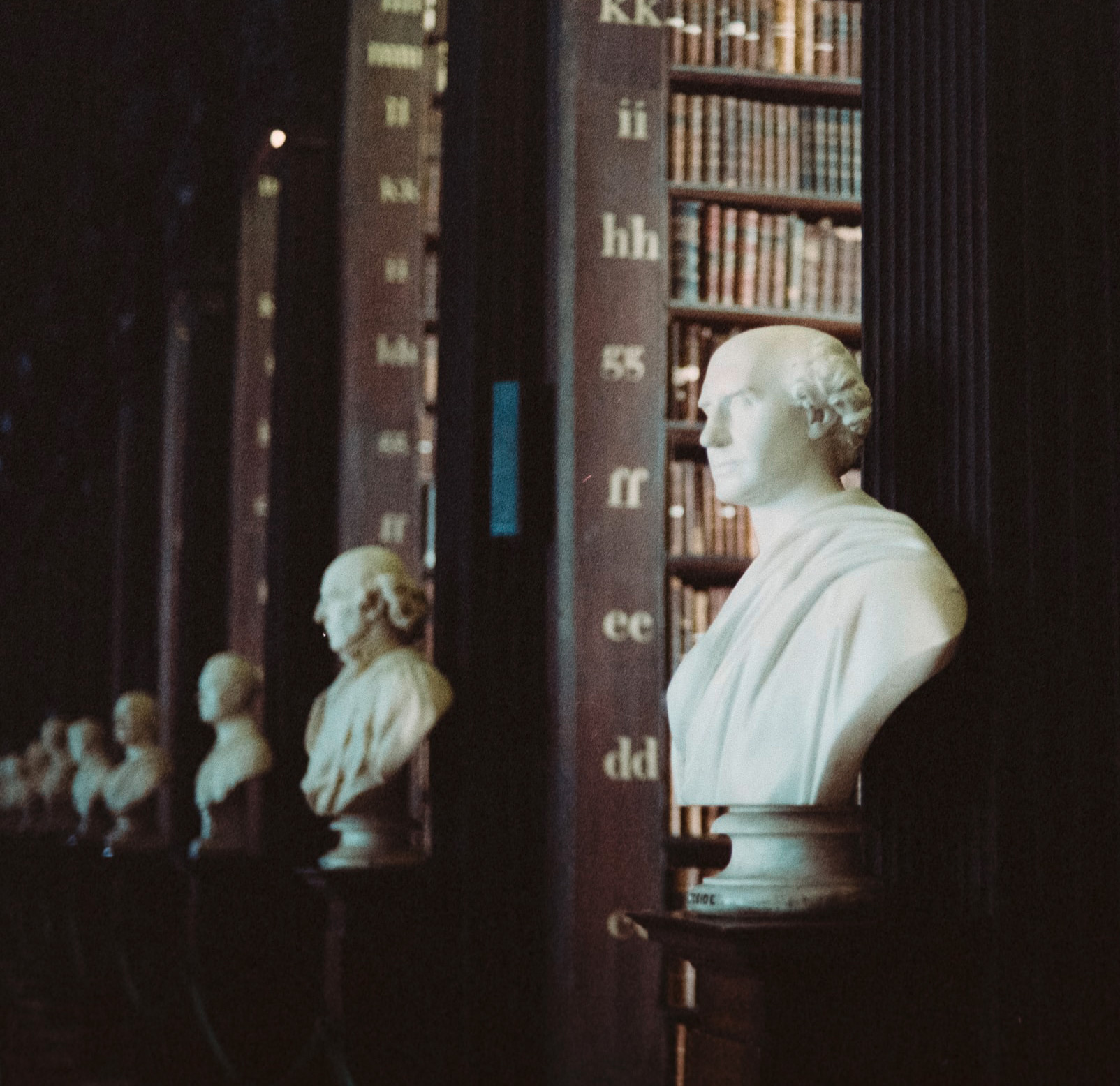

As most special collections have either a) considerable holdings from past donors related to well-established collecting fields or b) do not have the funds to participate in the open market to acquire ‘high point’ material, the focus of special collections has gone in a decidedly more eclectic, ‘Idea Oriented’, direction. This also reflects overall transitions of Humanities from defined departments to interdisciplinary research. This being the case, consider looking further afield to institutions nationally and internationally. Finally, once the collection is housed within special collections, your collection is now in the orbit of other objects and ideas.

Inheritance

The decision to bequeath one’s collection to family or friends can be rewarding. However, it is also the most complex. It assures that the collection will remain intact following your absence, however this is subject to change. The benefactor might have their own intentions and perceptions toward the collection. Assume nothing. This is something to come to terms with in deciding to go this route. Do as much as you can to convey the story of the collection to the benefactor and catalogue the collection in advance of your absence. For those who remain, your collection is more than items; you are woven in. As a result, handling the collection can (quite literally) prove difficult as high order analytical considerations that come with deaccessioning are nearly impossible in your absence. Make as many of these qualitative decisions as possible. You cannot assume that they will be in a position to do so or that they will simply understand the logic of the collection as you did.

Open up to those close to you about your collections, while also alluding to the collection’s relation to the outside world. If you choose to talk to them about the value of your collection, be realistic. The passing of the person impacts relatives’ or friends’ perceived value of the collection. It becomes much more than what the market wants, or what an appraiser has it as, because it was yours. Protect them from this line of thinking, keep good records, catalogue comparable prices of similar items from your collection.

IV. CONCLUSION

The rare bookseller Lorne Bair once said, “a hundred of anything is interesting.”

Like your rocks and marbles of childhood or broadsides and photographs of adulthood, if there is enough assembled, associations will start firing. He also admits, however, that, “Sometimes a garage full of Miatas,is a garage full of Miatas.”

Collecting is an action and a process. A collection is the result of real effort. Like a performance, it is founded on principles and routines, but it is also of the instance, of happenstance. As a result, no two collections are alike and there are as many collections as there are collectors. Our society often heralds the most expensive collections because it is easy to measure a dollar figure. The irony is that, oftentimes, these collections are the most conventional telling us nothing of the collector that we didn’t already know, nor about the field of collecting that the objects relate to. The collection’s only contribution is, hopefully, to enter into orbit with other objects, generating new associations.

Objects endure; their position within your collection will be brief. As a custodian of them, it is your obligation to document their place within the unique constellation your collection provides, preparing them to enter back into the outside world. Interesting collections tell us something about the collector as much as they do about the objects. Such transference can only be achieved by spending time with your collection and seriously considering the objects within it. Few things in life allow one to connect with objects on a personal and intellectual level quite like collecting.

Read also:

Lifecycles: Collecting & Collections. Part I – For the Curious

Lifecycles: Collecting & Collections. Part II – For the Collector

About Spencer W Stuart

Spencer W. Stuart provides advisory services to collections both private and institutional. He helps to facilitate collection development, cataloguing and deaccession strategies. His specialities include rare books, prints, and photography. In concert with his advising, Spencer is an active writer and lecturer on histories of the printed word for a variety of publications including The Book Collector and Amphora. As well as giving talks for both private and public events, Spencer also presents a monthly segment on Sheryl MacKay’s CBC Radio program “North by Northwest” as a Book Historian.

Spencer holds a master’s degree in the History of Art from the Courtauld Institute in London, England (recipient of the Director’s Award). Upon graduation he took a position with Bonhams Auctioneers where he worked closely with the North American Rare Books and Manuscripts department in Toronto and New York.

He is also an alumnus of the Colorado Antiquarian Book Seminars (’18) and has done course work at the Rare Book School (University of Virginia).

You can connect with Spencer via his website at http://spencerwstuart.ca/ or reach Spencer directly by phone (604.363.1012) or e-mail to discuss your specific needs.